1. Objective and Research Question

Part of its diversified activities, The Street Pulse team felt the pulse of the Lebanese citizens prior to the upcoming 2022 parliamentary elections. The team examined the following research question: “How are the most salient factors affecting the Lebanese citizens’ willingness to vote in the upcoming 2022 parliamentary elections?” This study focused on four factors, namely (i) the orientation on issues of public policy, (ii) the evaluations of the characteristics of both coalitions and candidates, (iii) clientelism, and (iv) the voter’s profile. The main objective is to shed light on why people will vote and what the implications of the results are.

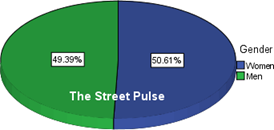

Figure 1. Distribution of the participants by gender and age

2. Research Methodology

In the framework of the pragmatic research philosophy, a deductive approach was applied with a conclusive research design (Holden & Lynch, 2004). A preliminary pilot study led to construct a questionnaire capable of probing 12 sub-factors affiliating to the aforementioned four factors such that: (i) orientation on issues of public policy is reflected by two dimensions, namely political and economic views of the electoral lists, (ii) the evaluations of the characteristics of both coalitions and candidates are reflected by fours dimensions, namely the potent representation of political parties, women, independent personalities, and traditional politicians on the electoral list, (iii) clientelism is reflected by two dimensions, namely the exchange of goods and services for political support, and (iv) voter’s profile is reflected by four dimensions, namely gender, age, political and confessional affiliations.

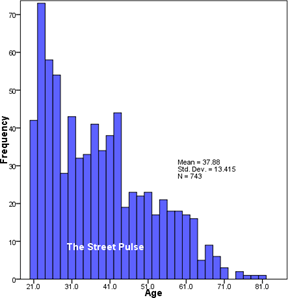

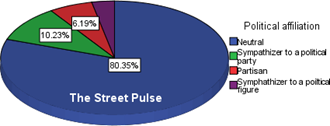

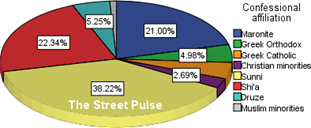

Figure 2. Educational attainment and political affiliation of the participants

Primary data were collected through an online survey, aligned with the self-selection sampling method, over the period January 27 to February 15, 2022 (Sharma, 2017). The initial 983 participants underwent a systematic screening process to mitigate response and social desirability biases, and were rendered down to 743. Figure 1 shows that the participants are almost evenly distributed between men and women, with an average age of 38 years and a standard deviation of 13 years. The eldest participant is 84 years old, while the youngest is 21 years old. Data for age are slightly positively skewed due to a minority of participants elder than 72 years, which compels the reporting of the median age of 36 years as a more reliable statistic than the mean. Figure 2 shows that about 52 percent of the participants hold a university degree and about 80 percent are neutral toward political parties and figures.

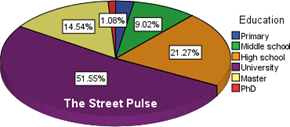

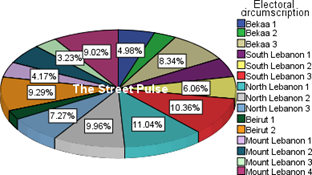

Figure 3. Distribution of the participants by electoral circumscription and confessional affiliation

Figure 3 shows the distribution of participants by electoral circumscription and by confessional affiliation.

3. Main Findings

The research question was investigated by a binary probit regression model with a choice of robust estimator for the covariance matrix to remedy for acquiescence and dissent biases (Alvarez & Nagler, 1998). The model was statistically significant, c2(9) = 70.108, p < .0001.

3.1 The Impact of Orientation on Issues of Public Policy

For the factor relevant to the orientation on issues of public policy, only the electoral list’s political views was found significant, while its economics view didn’t exhibit a clear statistical evidence to be reported hereafter. Moreover, people are more likely to vote for an electoral list with clear political views.

3.2 The Impact of the Evaluations of the Characteristics of both Coalitions and candidates

For the factor relevant to the evaluations of the characteristics of both coalitions and candidates, three out of four dimensions are found significant, namely the potent representation of political parties, independent personalities, and traditional politicians. People are more likely to vote for an electoral list endorsed by a political party and/or with a potent representation of independent personalities. Nevertheless, they are less likely to vote for a list with a potent representation of traditional politicians.

3.3 The Impact of Clientelism

For the factor clientelism, only the exchange of services was found significant, while the exchange of goods didn’t exhibit a clear statistical evidence to be reported hereafter. Furthermore, people are less likely to vote for an electoral list which strategy is based on the exchange of services it provides.

3.4 The Impact of Voter’s Profile

For the factor voter’s profile, one out of four dimensions was found significant, namely age. Elderly people are more likely to vote than younger ones, such that for each one year increase in age, the odds of voting increase by a factor of 1.012. Exempli gratia, a 35 years old citizen is about 5 times more likely to vote than a 30 years old citizen, which in turn is about 5 times more likely to vote than a 25 years old citizen, etc.

4. In-depth Interpretation of the Findings

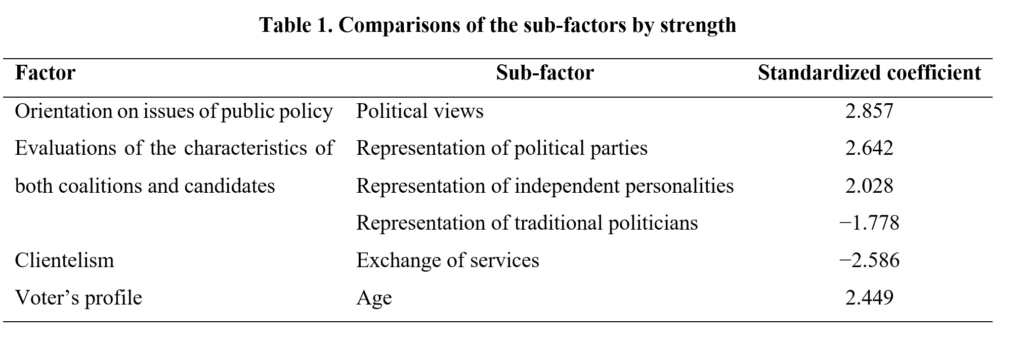

To summarize, there are six significant sub-factors, four of which have a positive influence on the participants’ willingness to vote, while the remaining two have a negative influence on voting behavior. Table 1 reports the standardized regression coefficients obtained for the significant sub-factors by which their strengths will be compared. Among the sub-factors that are estimated to have a positive influence on the willingness to vote, an electoral list’s political views is the most powerful, followed by the representation of a political party on the list. Among the sub-factors that are estimated to have a negative influence on the willingness to vote, an electoral list which strategy mainly depends on the exchange of services is more voters’ repelling than one with traditional politicians on board. Another interesting finding is when the standardized coefficients of the potent political parties and independent personalities’ representations are compared. Their ratio show that the estimated gap between politically affiliated and independent MPs in the 2022 elected parliament will be as narrow as 30 percent.

Table 1. Comparisons of the sub-factors by strength

5 Contact Information and Additional Information

The Street Pulse Team is willing to share its microdata with scholars and stakeholders upon request.

References

Alvarez, R. M., & Nagler, J. (1998). When politics and models collide: Estimating models of multiparty elections. American Journal of Political Science, 55-96.

Holden, M. T., & Lynch, P. (2004). Choosing the appropriate methodology: Understanding research philosophy. The marketing review, 4(4), 397-409.

Sharma, G. (2017). Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. International journal of applied research, 3(7), 749-752.